- Home

- Frank Froest

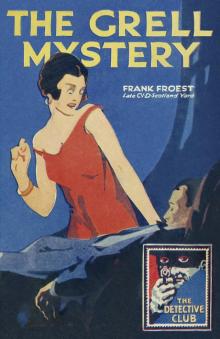

The Grell Mystery Page 7

The Grell Mystery Read online

Page 7

A medical man or a student of psychology might have found an analysis of her feelings interesting. She had reached the border-line of monomania, yet he would have been a daring man who would have called her absolutely insane. Except to Foyle she had said nothing of the feeling that obsessed her.

With cool deliberation she unlocked a drawer of her escritoire and picked out a dainty little ivory-butted revolver with polished barrel. It was very small—almost a toy. She broke it apart and pushed five cartridges into the chambers. With a furtive glance over her shoulder she placed it in her bosom, and then hastily returned to her chair by the fire and picked up a book. Her eyes skimmed the lines of type mechanically. She read nothing, although she turned the pages.

Presently she flung the book aside and, without ringing for a maid, dressed in an unobtrusive walking costume of deep black. She selected a heavy fur muff and transferred the pistol to its interior. Her fingers closed tightly over the butt. On her way to the door she was stopped by an apologetic footman.

‘There’s a lot of persons from the newspapers waiting out in the streets, Lady Eileen,’ he said.

‘Indeed!’ Her voice was cold and hard.

‘They might annoy you. They stop everyone who goes in or out.’

She answered shortly and stepped out through the door he held open. There was a quick stir among the reporters, and two of them hastily detached themselves and confronted her, hats in hand. She forced a smile.

‘It’s no use, gentlemen,’ she said. ‘I will not be interviewed.’ She looked very dainty and pathetic as she spread out her hands in a helpless little gesture. ‘Can I not appeal to your chivalry? You are besieging a house of mourning. And, please—please, I know what is in your minds—do not follow me.’

She had struck the right note. There was no attempt to break her down. With apologies the men withdrew. After all, they were gentlemen whose intrusion on a private grief was personally repugnant to them.

The girl reached Scotland Yard while Heldon Foyle was still in talk with Green. Her name at once procured her admission to him. She took no heed of the chair he offered, but remained standing, her serious grey eyes searching his face. He observed the high colour on her cheeks, and almost intuitively guessed that she was labouring under some impulse.

‘Please do sit down,’ he pleaded. ‘You want to know how the case is progressing. I think we shall have some news for you by tomorrow. I hope it will be good.’

‘You are about to make an arrest?’

The words came from her like a pistol-shot. A light shot into her eyes.

The detective shook his head. He had seen the look in her face once before on the face of a woman. That was at Las Palmas, in a dancing-hall, when a Portuguese girl had knifed a fickle lover with a dagger drawn from her stocking. Lady Eileen was scarce likely to carry a dagger in her stocking, but—his gaze lingered for a second on the muff, which she had not put aside. It was queer that she should not withdraw her hands.

‘I don’t say that. It depends on circumstances,’ he said gently.

Her face clouded. ‘I will swear that the man Fairfield killed him,’ she cried passionately. ‘You will let him get away—you and your red tape.’

He came and stood by her.

‘Listen to me, Lady Eileen,’ he said earnestly. ‘Sir Ralph Fairfield did not kill Mr Grell. Of that I have proof. Will you not trust us and wait a little? You are doing Sir Ralph a great injustice by your suspicions.’

She laughed wildly, and flung herself away from him.

‘You talk to me as though I were a schoolgirl,’ she retorted. ‘You can’t throw dust in my eyes, Mr Foyle. He has bought you. You are going to let him go. I know! I know! But he shall not escape.’

The superintendent stroked his chin placidly. As if by accident he had placed himself between her and the door. He had already made up his mind what to do, but the situation demanded delicate handling.

‘You will regret this when you are calmer,’ he said mildly.

He was uncertain in his mind whether to tell the distraught girl that her lover was not dead—that the murdered man was a rogue whom probably she had not seen or heard of in her life. He balanced the arguments mentally pro and con, and decided that at all hazards he would preserve his secret for the present. She took a step towards the door. She had drawn herself up haughtily.

‘Let me pass, please,’ she demanded.

He did not move. ‘Where are you going?’ he asked. Her eyes met his steadily.

‘I am going to Sir Ralph Fairfield—to wring a confession from him, if you must know,’ she said. ‘Let me pass, please.’

‘I will let you pass after you have given me the pistol you are carrying in your muff,’ he retorted, holding out his hand.

Then the tigress broke loose in the delicately brought-up, gently nurtured girl. She withdrew her right hand from her muff and Foyle struck quickly at her wrist. The pistol clattered to the floor and the man closed with her. It needed all his tremendous physical strength to lift her bodily by the waist and place her, screaming and striking wildly at his face with her clenched fists, in a chair. He held her there with one hand and lifted one of the half-dozen speaking-tubes behind his desk with the other.

In ten minutes Lady Eileen Meredith, in charge of a doctor and a motherly-looking matron hastily summoned from the adjoining police station in Cannon Row, was being taken back to her home in a state of semi-stupor. Foyle picked up the dainty little revolver from the floor and, jerking the cartridges out, placed it on the mantelpiece.

‘You can never tell what a woman will do,’ he said to himself. ‘All the same, I think I have saved Ralph Fairfield’s life today.’

CHAPTER XV

HELDON FOYLE was more deeply chagrined than he would have cared to admit by the disappearance of Waverley. It was not only that one of the most experienced men of the Criminal Investigation Department had fallen into a trap and so placed his colleagues in difficulties. The very audacity of the coup showed that the department was matched against no ordinary opponents. There is a limit even to the daring of the greatest professional criminals. If there were professionals acting in this business, reflected the superintendent, the idea was none of theirs. Besides, no professional would have written the letter threatening the Yard. That was no bluff—the finger-prints proved that. To hold a Scotland Yard man as a hostage was a game only to be played by those who had much at stake.

Only one man shared Heldon Foyle’s confidence. That was Sir Hilary Thornton. To the Assistant Commissioner he talked freely.

‘It’s an ugly job for us, sir, there’s no disguising that. Naturally, they count on us keeping our mouths shut about Waverley. It’s lucky he’s not a married man. If the story of the way he was bagged becomes public property we shall be a laughing-stock, even if we get him out of his trouble. And if we don’t, the scandal will be something worse.’

‘Yes. It’s bad—bad,’ agreed the Assistant Commissioner. ‘The Press must not hear of this.’

‘Trust me,’ said Foyle grimly. ‘The Press won’t.’

‘I don’t like this affair of Lady Eileen Meredith,’ went on Sir Hilary. ‘After all, she has a good right to know the truth. Wouldn’t it be better to let her know that Grell is alive?’

Foyle jingled some money in his trousers pocket.

‘I hate it as much as you do, Sir Hilary. I can’t take any chances, though. Grell knows we know he is alive. When he finds that this girl has not been told he may try to communicate with her, and then we may be able to lay hands on him and Ivan, and so clear up the mystery. There’s another thing. As far as our inquiries through his solicitors and the bank go, he couldn’t have had much ready cash on him. He’ll try to get some sooner or later—probably through his friends. He’s already tried to approach Fairfield.’

‘I see,’ agreed the other in the tone of a man not quite convinced. ‘Now, when are you going down to Grave Street again? You’ll want at least a dozen men.’

&n

bsp; ‘There won’t be any trouble at Grave Street,’ answered Foyle with a smile; ‘and if there is, Green and I will have to settle it. More men would only be in the way. Our first job is to get hold of Waverley.’

‘But only two of you! Grave Street isn’t exactly a nice place. If there is trouble—’

‘We’ll risk that, sir,’ said Foyle, stiffening a trifle.

He went back to his own room and signed a few letters. Some words through a speaking-tube brought Green in, stolid, gloomy, imperturbable. The chief inspector accepted and lit a cigar. Through a cloud of smoke the two men talked for a while. They were going on a mission that might very easily result in death. No one would have guessed it from their talk, which, after half an hour of quiet, business-like conversation, drifted into desultory gossip and reminiscences.

‘Sir Hilary wanted me to take a dozen men,’ said Foyle. ‘I told him the two of us would be plenty.’

‘Quite enough, if we’re to do anything,’ agreed Green. ‘I wouldn’t be out of it for a thousand. Poor old Waverley and I have put in a lot of time together. I guess I owe him my life, if it comes to that.’

Foyle interjected a question. The chief inspector lifted his cigar tenderly from his lips.

‘It was in the old garrotting days,’ he said. ‘Waverley and I were coming down the Tottenham Court Road a bit after midnight—just off Seven Dials. There were half-a-dozen men hanging about a corner, and one of them tiptoed after us with a pitch plaster—you’ll remember they used to do the stuff up in sacking and pull it over your mouth from behind. I never noticed anything, but Waverley did. The man was just about to throw the thing over me when Waverley wheeled round and hit him clean across the face with a light cane he was carrying. The chap was knocked in the gutter and his pals came at us with a rush. A hansom driver shouted to us to leave the man in the roadway to him, and hanged if he didn’t drive clean over him with the near-side wheel. That gave us our chance. We hopped into the cab and got away without staying to see if anyone was hurt. But if Waverley hadn’t hit out when he did I’d have been a goner.’

‘I had a funny thing happen to me once in the Tottenham Court Road,’ said Foyle reminiscently. ‘I was an inspector then and big Bill Sladen was working with me—he had a beautiful tenor voice, you will remember. We were after a couple of confidence men and had a man we were towing about to identify them. Well, we got ’em down to a saloon bar near the Oxford Street end, but I daren’t go in because they knew me. It was a bitter cold night, with a cold wind and snow and sleet. So I stayed on the opposite side of the road and induced Bill to go over and sing “I am but a Poor Blind Boy”, in the hope that our birds would call him in and give him a drink. He hadn’t been at it five minutes before a fiery, red-headed little potman had knocked him head over heels in the gutter and told him to go away. Bill could have broken the chap in two with his little finger, but he daren’t do anything. He came over to me and I sent him back again. This time he did get invited inside. And there he stayed for a full hour, while the witness and I stood shivering and wet and miserable in the snow. We could hear him laughing and singing with the best of ’em. They wouldn’t let him come away. It was not until I took all risks and marched in with the witness and arrested them that they tumbled to the fact that he wasn’t a real street singer.’ He glanced at his watch. ‘You’d better go and have a rest, Green. Meet me here at half-past twelve. We’ll take a taxi to Aldgate and walk up from there. And, by the way, here’s a pistol. I needn’t tell you not to use it unless you’ve got to.’

CHAPTER XVI

A BITTER wind was sweeping the Commercial Road, Whitechapel, as the two detectives, each well muffled up, descended from their cab and walked briskly eastwards. Save for a slouching wayfarer or two, shambling unsteadily along, and little groups gathered about the all-night coffee-stalls, the roads were deserted. Neither man had attempted any disguise. It was not necessary now.

As they turned into Grave Street they automatically walked in the centre of the roadway. There are some places where it is not healthy to walk at night on shadowed pavements. They moved without haste and without loitering, as men who know exactly what they have to do. From one of the darkened houses a woman’s shrill scream issued full of rage and terror. It was followed by a man’s loud, angry tones, the thud of blows, shrieks, curses, and brutal laughter. Then the silence dropped over everything again. The two men had apparently paid no heed. Even had they been inclined to play the part of knights-errant in what was not an uncommon episode in Grave Street, they knew that the woman who had been chastised would probably have been the first to turn on them.

There was a side entrance to 404A, which was the newspaper shop that Foyle had cause to remember. He struck the grimy panel sharply with his fist and waited. There was no reply. Again he knocked, and Green, unbuttoning his greatcoat, flung it off and laid it across his arm. He could drop it easily in case of an emergency. Still there was no answer to the knock.

‘Luckily I swore out a search warrant,’ muttered Foyle, and searched in his own pockets for something. It was a jemmy of finely tempered steel gracefully curved at one end. He inserted it in a crevice of the door and, leaning his weight upon it, obtained an irresistible leverage. There was a slight crack, and it swung inwards as the screws of the hasp drew. The two men stepped within and, closing the door, stood absolutely still for a matter of ten minutes. Not a sound betrayed that their burglarious entry had alarmed anyone.

Presently Green made a movement, and a vivid shaft of light from a pocket electric lamp played along the narrow uncarpeted passage. The superintendent gripped his jemmy tightly and turned towards the dirty stairs. Then the light vanished as quickly as it had flared up, and from above there came a sound of shuffling footsteps. Even Heldon Foyle, whom no one would have accused of nervousness, felt his heart beat a trifle more quickly. He knew that if he were as near the heart of the mystery as he believed any second might see shooting. Penned as he and his companion were in the narrow space of the passage barely three feet wide, a shot fired from above could scarcely miss.

Crouching low, he sprang up the narrow staircase in three bounds, making scarcely a sound. On the landing above he wound his arms tightly about the person whose movements he had heard and whispered a quick, tense command.

‘Not a word, or it will be the worse for you. Let’s have a light, Green.’

The prisoner kept very still, and Green flashed a light on his face. It was that of a man of forty or so, with pronounced Hebrew features. His greasy black hair was tangled in coarse curls, and a smooth black moustache ran across his upper lip. A pair of shifty eyes were fixed fearfully on Foyle, and the man murmured something in a guttural tongue.

‘We are police officers. How many people are there in this house?’ demanded Foyle sternly, in a low voice. ‘You may as well answer in English. Quietly, now.’

He had released his hold round the Jew’s waist, but stood with the jemmy dangling by his side and with ears cocked ready for any sound. Green had climbed the stairs and stood by his side.

Domiciliary visits are unfrequent in England, but the Jew was not certain enough to stand upon a legal technicality. As a matter of fact, the search warrant would have met the difficulty. He cringed before the two men, whose faces he could not see, for Green had thrown his wedge of light so that it showed up the man’s sallow face and left all else in darkness.

‘I do not know why you have come,’ he answered, forming each word precisely. ‘I have done nothing wrong. I am an honest newsagent. There is only my wife, daughter, son, lodger in house.’

‘You are a receiver of stolen goods,’ answered Foyle, something, it must be confessed, at a venture. ‘Don’t trouble to deny it, Mr Israels. We’re not after you this time—not if you treat us fairly. What about this lodger of yours? Have you bought him a typewriter lately?’

‘Yes—yes. I help you all I can,’ protested the Jew, with an eagerness that deceived neither of the detectives. There is no class of

liar so abysmal as the East-end criminal Jew. They will hold to a glib falsehood with a temerity that nothing can shake. If there is no necessity to lie, they lie—for practice, it is to be presumed. The best way to extract a truth is to make a direct assertion by the light of apparent knowledge and so sometimes obtain assent. Foyle knew the idiosyncrasies of the breed. Hence the threat in his demand.

‘I bought a typewriter—yes,’ went on Israels. ‘I think he was honest. Didn’t seem as though police after him.’

‘Which room is he in?’

Israels jerked a thumb upwards. ‘Next landing. Door on left,’ he ejaculated nervously.

The superintendent pushed by the man. He knew that the critical moment had come. With his quick judgment of men he had summed up Mr Israels. Whatever the Jew’s morals, it was evident that he had a wholesome respect for his own oily skin. He would not risk himself to save the neck of another man. Foyle’s intentions were simple. He would steal quietly up the second flight of stairs, burst the door open if it were locked, and seize the man he was in search of in his sleep. But his plans were frustrated.

He had not taken two steps when a woman peeped from an adjoining room. He caught one glimpse of her in the semi-darkness with a police whistle at her lips. He sprang forward, and as he did so a shrill, ear-piercing blast rang out. Green was close behind him.

She shrieked as the detective tore the whistle from her, and he felt her slender figure entwine itself about him. Down he went, with his companion on top of him, and another woman’s loud hysterical cries added to the pandemonium. Foyle picked himself up and, lifting the girl bodily, flung her without ceremony into the room from which she had emerged. From above a voice shouted something, and a knife whizzed downwards and struck quivering in the bare boards of the landing, grazing Green’s shoulders.

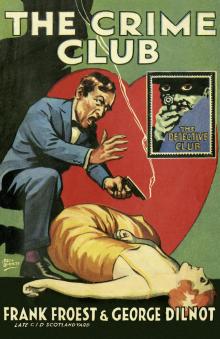

The Crime Club

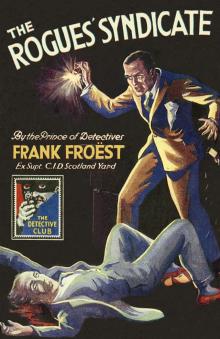

The Crime Club The Rogues' Syndicate

The Rogues' Syndicate The Grell Mystery

The Grell Mystery