- Home

- Frank Froest

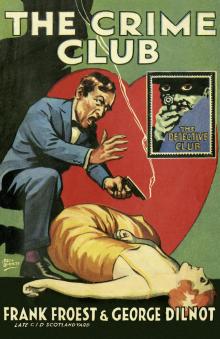

The Crime Club

The Crime Club Read online

Copyright

Published by COLLINS CRIME CLUB

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street,

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by Eveleigh Nash 1915

Published by The Detective Story Club for Wm Collins Sons & Co. Ltd 1929

Introduction © David Brawn 2016

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1929, 2016

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008137335

Ebook Edition © June 2016 ISBN: 9780008137342

Version: 2016-04-28

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

Chapter I: The Crime Club

Chapter II: The Red-Haired Pickpocket

Chapter III: The Man With the Pale-Blue Eyes

Chapter IV: The Maker of Diamonds

Chapter V: Creeping Jimmie

Chapter VI: The Mayor’s Daughter

Chapter VII: A Meeting of Greeks

Chapter VIII: The Seven of Hearts

Chapter IX: The Goat

Chapter X: Pink-Edged Notepaper

Chapter XI: The String of Pearls

Chapter XII: The ‘Con’ Man

Chapter XIII: Crossed Trails

Chapter XIV: The Dagger

Chapter XV: Found—a Pearl

The Crime Club

The Detective Story Club

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION

WHEN The Crime Club was first published by Eveleigh Nash in 1915, little did the authors—both of them ex-policemen—know that the book’s title would become synonymous with detective publishing for the next 100 years.

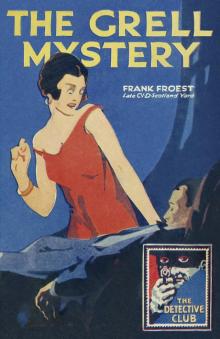

Frank Froëst had risen through the ranks of the Metropolitan Police, attaining the position of Superintendent of the CID in 1906. He had become famous for his involvement in a number of high-profile international incidents, including the mass arrest in South Africa of more than 400 of the Jameson Raiders in 1896—the biggest mass arrest in British history—and for bringing high-profile villains such as society jewel-thief ‘Harry the Valet’ and the notorious Dr Crippen to justice. (More of Froëst’s exploits are discussed in Tony Medawar’s introduction to The Grell Mystery, also in this series.) Froëst retired in 1912, moving to Somerset where he joined the County Council and became a magistrate. Putting his 33-year experience in the police service to good use, he also turned to writing, and his detective novel The Grell Mystery (1913) proved popular with readers, who felt that its author was giving them an authentic insight into the detail of real police work—a genre that would become referred to as the ‘police procedural’.

Speculation that Froëst had help from a professional writer to produce a debut novel as fine as The Grell Mystery is given some credence by his sharing the byline on his two subsequent books with writer George Dilnot. Turning to journalism after six years in the army and subsequent service in the police, Dilnot’s first major book, Scotland Yard: The Methods and Organisation of the Metropolitan Police (1915), owed a great deal for its detailed content to the recently retired Froëst. The book was one of the earliest attempts to make public the inside workings of ‘the finest police force in the world’, which at that time employed 20,000, and must have been an invaluable resource for early detective writers. Froëst himself is name-checked numerous times, and comes across as the epitome of determination, organisation and innovation.

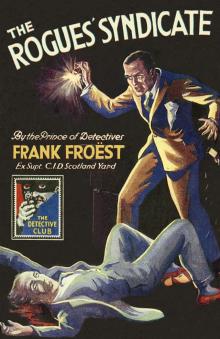

Whether or not Dilnot did ghost-write The Grell Mystery as a favour to his former boss, by the time Froëst’s other detective novel was published, The Rogues’ Syndicate (1916), they were sharing equal billing. First serialised in the US as The Maelstrom in the magazine All-Story Weekly over six weeks in March and April 1916, the book marked the end of Froëst’s short writing career, although his name lived on in reprints and in silent movies of both The Grell Mystery and The Rogues’ Syndicate in 1917, the latter film retaining its magazine title of The Maelstrom.

In between the two novels came The Crime Club, a collection of eleven detective stories (plus a prefatory chapter) that had originally appeared in the monthly The Red Book Magazine between December 1914 and November 1915. The stories were linked by the conceit of a secret London club located off the Strand where international crime fighters would go to help solve and also share tales of their most outlandish cases. Although the idea of a fictional detectives’ club was not entirely new, previous instances—for example Carolyn Wells’ five stories about the International Society of Infallible Detectives, starting with ‘The Adventure of the Mona Lisa’ in January 1912—brought together pastiches of well-known sleuths such as Sherlock Holmes and Arsène Lupin, whereas The Crime Club featured all-new creations, with the exception of Froëst’s own Heldon Foyle from The Grell Mystery, who appeared in ‘The String of Pearls’.

The stories were collected and published in book form as The Crime Club by Eveleigh Nash in 1915, apparently before their run in The Red Book Magazine had ended. In 1929, keen to have a book of short stories in the initial run of their new sixpenny Detective Story Club series, William Collins licensed the rights from Nash to print a cheap edition of the book, which was published in July 1929; The Grell Mystery and The Rogues’ Syndicate would follow within a year. Like many of the other early books in that series, The Crime Club also appeared in Collins’ ‘Piccadilly Novels’ imprint as an exclusive edition for Boots Pure Drug Co. Ltd (who also sold books), using the same typesetting and with the painting from the back of the Detective Story Club jacket transposed to the front.

Frank Froëst gave up writing in 1916 when his wife died, focusing on council work until the onset of blindness forced him into retirement and a convalescent home in Weston-super-Mare, where he died in 1930 at the age of 71. However, his association with George Dilnot continued, helping him to research his landmark book, The Story of Scotland Yard (1927), a completely new and expanded version of his first book. Dilnot continued to write about the police and true crime, including two volumes in Geoffrey Bles’s Famous Trials series, on which he was Series Editor, and revisited the subject of the Yard again with New Scotland Yard in 1938. But he was much more prolific in fiction, writing another 16 novels under his own name, with series characters including Jim Strang, Horace Elver, Val Emery and Inspector Strickland, plus three books for the popular Sexton Blake series.

When the reissue of The Crime Club came out in 1929, George Dilnot was therefore still very active and by then better known to readers than Frank Froëst. The book enjoyed a new lease of life, and within a year there were 19 titles in the Detective Story Club series. One of the secrets of its success, like so many cheap editions being published at that time, was their availability in newsagents and tobacconists as well as traditional bookshops (many of whom frowned upon the concept of cheap editions and would not stock them). Their success convinced Collins to chase more s

ales from this market by launching its own monthly magazine, and in June 1930 ‘The Detective Story Club Limited’ published a bold offshoot: Hush Magazine.

Like the book series that inspired it, Hush (the word Magazine being added to its title from issue No. 3) sold for just sixpence and sported brightly coloured covers, usually featuring the clichéd dame in distress, and contained in its 128 pages a mixture of fiction stories and non-fiction articles, some with new line drawings, and a small amount of advertising. The covers proudly proclaimed that the monthly magazine was ‘Edited by Edgar Wallace’, and indeed every issue began with a Wallace story—and usually a page advertising his new Collins book The Terror and/or The Educated Man. But like the more famous and longer-running Edgar Wallace Mystery Magazine that began in 1964, Wallace was not involved; the compilation and editing was by an uncredited George Dilnot. He adapted his own The Story of Scotland Yard, serialised every month from issue No. 3, and recycled some of his stories from The Red Book Magazine, interestingly dropping Frank Froëst’s name from them.

Hush Magazine ceased publication after only a year with No. 13 dated June 1931. There was no indication inside that it would be the last, with two ‘Next Month …’ adverts appearing in its pages. Collins was not a magazine publisher, and either the effort of compiling a varied and illustrated monthly collection of stories had got too much for them, or the circulation figures simply dropped below a sustainable level. Over its run, however, George Dilnot and the team had assembled a respectable if increasingly predictable mix of content, with regular reprints of fiction stories by stalwarts including J. S. Fletcher, Arthur B. Reeve, Sydney Horler, H. de Vere Stacpoole, Maurice Leblanc, G. D. H. & M. Cole, Edgar Allan Poe and even H. G. Wells. The most notable inclusion was a run of five Miss Marple stories by Agatha Christie beginning in November 1930, the month following the character’s very first book appearance in The Murder at the Vicarage, and which would not themselves appear in a book until The Thirteen Problems in June 1932. The publication of one-off detective stories by unknown authors in amongst these popular names provided some interesting reading, but this aspect of the magazine was soon curtailed as it was presumably the well-known names, emblazoned on the covers, who guaranteed sales.

Undaunted after a year on the magazine, George Dilnot returned to writing novels with The Thousandth Case (1932), averaging a book a year throughout the 1930s. His final novel was a Nazi war thriller, Counter-Spy, published by Geoffrey Bles in 1942. At almost 60 years old, Dilnot appears like Frank Froëst to have decided to stop writing ahead of retirement, and died nearly a decade later on 23 February 1951 in East Molesey in Surrey, aged 68.

Of all their books, The Crime Club is probably the least well remembered of any by Froëst or Dilnot, such is the fate of collections of short stories in most writers’ careers. Largely typical of detective stories of their era, the most interesting now is ‘The Red-Haired Pickpocket’ (from The Red Book Magazine, February 1915) as a rare example of a plot being ‘borrowed’ by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. The solution to ‘The Problem of Thor Bridge’, published in The Strand Magazine in two parts in February and March 1922, and collected in The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes, is so similar, even down to the small mark on the side of the bridge, that it doesn’t need Sherlock Holmes to deduce that Conan Doyle must have read the Froëst and Dilnot story.

In addition to the dozen stories that comprised The Crime Club, the pair collaborated to write three more in the same vein also for The Red Book Magazine: ‘Crossed Trails’, ‘The Dagger’ and ‘Found—A Pearl’ appeared in the February, August and September issues of 1916. One hundred years later, they are reprinted here for the first time in book form.

If the stories were forgotten, at least their collective title was to live on in another Collins publishing initiative even more ambitious than Hush Magazine—and one with decidedly more success. On 6 May 1930 Philip MacDonald’s detective novel The Noose was the first of the monthly ‘Recommended’ titles to be published by a brand new imprint—the Crime Club. But that is another story.

DAVID BRAWN

March 2016

I

THE CRIME CLUB

YOU will seek in vain, in any book of reference, for the name of the Crime Club. Purists may find a reason in the fact that a club without subscriptions, officials, or headed notepaper is no club at all. The real explanation probably is that the club avoids advertisement. It is content to know that even in its obscurity it is the most exclusive club in the world.

No member is ever elected; no member ever resigns. Yet the wrong man is never admitted, the right man rarely excluded. Its members are confined not only to one profession but to the picked men even of that profession. Its headquarters is as unostentatious as its existence—a little hotel handy to the Strand wherein some years ago Forrester and Blake of the Criminal Investigation Department had discovered a discreet manager, a capable chef, and a back dining-room.

The progress of time, and the tact of the manager, had conceded a sitting-room with a dozen or so big and deep arm-chairs. From noon onwards, the two apartments had become sacred to the Crime Club.

Quiet, comfortable-looking men dropped in for luncheon or dinner and a chat that was as likely to cover gardening or politics as murder or burglary. Perhaps the only trait that they showed in common was some indefinable trick of humour that lurked in their faces. An experienced detective has seen too much to take himself too seriously.

The rank and file of the world’s detective services have no entrée to the Crime Club. Only men whose repute is beyond suspicion are among its members. Strictly, it is an international club, for although its most determined frequenters are a dozen Scotland Yard men, there is always a sprinkling of detectives from abroad to be found there. You may see perhaps a thin, hawk-faced Pinkerton man grimly chaffing an excitable, black-bearded little Italian, none other than the redoubtable Cipriano of the Italian Secret Service. In the group about the fire are Kuntze of Berlin—a stolid, bovine-faced man whose looks belie the subtlety of a tempered brain; Heldon Foyle, the tall, urbane superintendent of the Criminal Investigation Department; a jolly-faced, fat officer from the Central Office in New York; the slim-built, grey-moustached commissioner of a great overseas police force—himself an old Scotland Yard hand; a sprucely-dressed Frenchman from the Service de Sûreté; a provincial chief constable; a private inquiry agent so fastidious about the selection of his clients that he is making only a couple of thousand a year instead of the five thousand that could be his if he did not object to dirty hands; and a couple of chief inspectors from the Yard.

Search the newspaper files of the world and you will here and there get a hint of remarkable things done by these men—of supreme feats of organisation in pursuit, of subtleties in unveiling mysteries, of bulldog courage and tenacity, of quick-witted resource in emergencies. You will not find all the truth there because there are sometimes happenings of which it is not well all the truth should be known; but you will gather much from the manner of men they are.

Sometimes, over coffee and cigars, the talk may drift to some of the affairs of the profession. Some of these find a place in the present chronicles.

II

THE RED-HAIRED PICKPOCKET

JIMMIE ILES was ‘some dip’. That was how he would have put it himself. In the archives of the New York Central Detective Bureau the description was less concise, but even more plain: ‘James (Jimmie) Iles, alias Red Jimmie, alias, etc … expert pickpocket …’

And Red Jimmie, whose hair was flame coloured and whose indomitable smile flashed from ear to ear on the slightest provocation, would have been lacking in the vanity of the underworld if he had not been proud of his reputation at Mulberry Street. Nevertheless, fame has its disadvantages, and though he was on friendly terms with the headquarters staff individually, he hated the system that had of late prevented his applying his undoubted talents to full profit.

England beckoned him—England, where he could make a fresh start with the

past all put behind him. Do not make a mistake: Jimmie had no intention of reform. But in England there were no records, and consequently the police would not be allowed points in the game. It would be hard, therefore, if an energetic, painstaking man could not pick up enough to keep him in bread and butter.

Behold Jimmie, therefore, a first-class passenger on the S.S. Fortunia—‘Mr James Strickland’ on the passenger list—a suit in the Renaissance style of architecture built about him, the skirts of his coat descending well towards his knees, his peg-top trousers roomy and with a cast-iron crease. Behold him explaining for the fiftieth time to one of his sometime ‘stalls’ the reason that had driven him from God’s own country.

‘I’m too good-natured. That’s what’s the matter with me. The bulls are right on to me. If I carried a gun or hit one of ’em, like Dutch Fred, I might get away with it sometimes. But I can’t do it. They’re good boys, though they’ve got into a kind of habit of pulling me whenever they’re feeling lonely. I can’t go anywhere without a fourt’ of July procession of sleuths taggin’ after me— Holy Moses, there’s one there now. How do you do, Mr Murray? Say, shall we find if there’s a saloon?’

Detective-Sergeant Murray grinned affably. ‘Not for mine, Jimmie old lad. I’ve got that kind of lonesome feeling. Won’t you see me home?’

Jimmie thrilled with a tremor of familiar apprehension. ‘Honest to Gawd, I ain’t done a thing,’ he declared earnestly. ‘You’re only jollying, Mr Murray?’

The officer laughed and vanished. Jimmie decided to make himself inconspicuous till the vessel sailed. Luckily for his peace of mind, he did not know that the Central Office was paying him the compliment of a special cable in order that he might receive proper attention when he landed.

The Crime Club

The Crime Club The Rogues' Syndicate

The Rogues' Syndicate The Grell Mystery

The Grell Mystery