- Home

- Frank Froest

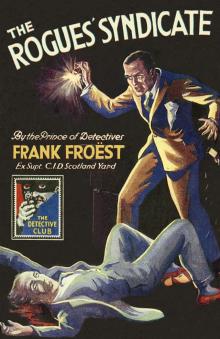

The Rogues' Syndicate

The Rogues' Syndicate Read online

‘THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB is a clearing house for the best detective and mystery stories chosen for you by a select committee of experts. Only the most ingenious crime stories will be published under the THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB imprint. A special distinguishing stamp appears on the wrapper and title page of every THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB book—the Man with the Gun. Always look for the Man with the Gun when buying a Crime book.’

Wm. Collins Sons & Co. Ltd., 1929

Now the Man with the Gun is back in this series of COLLINS CRIME CLUB reprints, and with him the chance to experience the classic books that influenced the Golden Age of crime fiction.

Copyright

COLLINS CRIME CLUB

an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by Eveleigh Nash 1916

Published by The Detective Story Club Ltd for Wm Collins Sons & Co. Ltd 1930

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1930, 2018

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008137717

Ebook Edition © May 2018 ISBN: 9780008137724

Version: 2018-04-17

Dedication

DEDICATED TO

WILLIAM ALLAN PINKERTON,

America’s greatest Crime Investigator, to whom one of the writers will be ever indebted for the great and valuable assistance offered him throughout his official career.

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Introduction

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Chapter VII

Chapter VIII

Chapter IX

Chapter X

Chapter XI

Chapter XII

Chapter XIII

Chapter XIV

Chapter XV

Chapter XVI

Chapter XVII

Chapter XVIII

Chapter XIX

Chapter XX

Chapter XXI

Chapter XXII

Chapter XXIII

Chapter XXIV

Chapter XXV

Chapter XXVI

Chapter XXVII

Chapter XXVIII

Chapter XXIX

Chapter XXX

Chapter XXXI

Chapter XXXII

Chapter XXXIII

Chapter XXXIV

Chapter XXXV

The Detective Story Club

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION

FOR the lover of a really exciting detective story, here is good fare. For those a little tired of New York’s Underworld, here is more familiar ground: west-end streets and restaurants; respectable suburban villas; purlieus of Bloomsbury—an east-end we know to be true. Here are no puppets, but human, vivid figures playing out a drama of love and hate and greed, the sleuths of Scotland Yard hot on their trail and the shadow of the hangman’s noose before their eyes.

Ex-Superintendent Frank Froëst tells his story in a straightforward way. There are no hidden clues, no sudden dénoue-ments to put the reader deliberately on a false trail. He shares the excitement of the hunt, knows all there is to know, and has every chance to spot the murderer and solve the mystery of the forged cheques.

The adventures of Jimmie Hallett are sufficiently exciting in all conscience to satisfy the most exacting of detective story ‘fans’. Against a familiar London background, we have here a tale of breathtaking adventure—knifing, arson, racing-taxicabs, and shooting-to-kill. Can Weir Menzies, that genial detective with the churchwarden manner, even with all the resources of Scotland Yard behind him, succeed in outwitting a gang of international crooks of whose very numbers he is ignorant?

His efforts to unravel the tangle lead him to the unsavoury atmosphere of Shadwell and the docks. His quarry, after slipping through the cordon of police, is run to earth in a Chinese opium den. There is a cellar in Brixton, a furiously-driven taxi with a dead woman for fare—in fact, a constant succession of thrills.

Apart from the tale, to make the acquaintance of Mr Weir Menzies is a pleasure in itself. Weir Menzies, the model husband, the respectable and respected citizen of Tooting, with his dog and his roses and his dislike of late hours; Weir Menzies, with his calm, unhurried manner, refusing to be rushed, refusing to be ruffled, relying on perseverance and dull routine and plain common sense. Surely here is a detective after everyone’s heart.

Detection as a science and not a freak accomplishment is expounded in this story with a wealth of convincing argument. As a vindication of official procedure it is worth reading alone. It is written with genuine knowledge of the methods of police detection, sometimes dull and laborious in themselves: the careful sitting of a mass of irrelevant detail; the intelligent consideration given to the most trivial scrap of information; the interesting survey of the case from time to time by highly-placed officials (the C.I.D. believes firmly that two heads are better than one, and sometimes three than two); then finally the close and oft-repeated scrutiny of the points of the case when it takes definite shape in their hands, to ensure that it is proof against the slings and arrows of the defending counsel.

It is a fact of real life, in this country at least, that a criminal may—and not infrequently does—escape justice, in spite of widespread belief in his guilt, through the inability of the police to bring definite proof in support of their theory. A recent tightening of the law has still further restricted their powers of questioning suspects—never at any time in England have they been permitted to indulge in the protracted and intensive methods of examination in vogue on the continent and in America—and thus made it increasingly difficult to obtain the proofs necessary to bring the criminal to justice.

The Rogues’ Syndicate illustrates clearly the difficulty under which the police sometimes labour in this respect—their inability to obtain sufficient evidence to prove their charge to a jury—and as an intelligent exposition of this aspect of our criminal law should be read with enjoyment by everyone interested in crime and detection.

Accuracy of detail is ensured by the fact that the author, ex-Superintendent Frank Froëst, was over thirty years at Scotland Yard. His triumphs range from his successful round-up of Jabez Balfour in the Argentine in connection with the Liberator frauds to his equally dramatic success in the Crippen case, the sensational arrest of Dr Crippen—in which wireless played an important part being planned by this resourceful detective in his room at Scotland Yard.

THE EDITOR

FROM THE ORIGINAL DETECTIVE STORY CLUB EDITION

April 1930

CHAPTER I

HALLETT blundered into an unlit lamp-post, swore with fervour, and stood for a second peering for some i

dentifiable landmark in the black blanket of fog that shrouded the street. Where he stood, a sluggish, dense drift had collected, for, following the treacherous habit of London fogs, it lay in patches. About him he could hear ghostly noises of traffic muffled and as from afar, but whether the sounds came from before or behind, from right or left, was more than his bewildered senses could fathom.

For the last ten minutes he had been walking in a spectral city among spectres. A by-street had trapped him, and no single wayfarer had come within his limited area of sight. He lifted his hat and rubbed his head perplexedly as he came to the conclusion that he was lost. It was as though London had set out to teach the young man from New York a lesson. The fog had beaten him.

‘Expect I shall get somewhere in time,’ he muttered, and strode doggedly on.

He had gone perhaps a dozen yards, when from ahead a quick burst of angry voices broke out. Then there came a running of feet on a sodden pavement. Hallett came to a stop, listening. The fog seemed to thin a trifle.

Out of the thickness the outlines of a woman’s figure loomed vaguely. She was running swiftly and easily with lithe grace. As she noted the motionless figure of Hallett, she swerved towards him, and he caught the hurried pant of her breath—caused rather, he judged, by emotion than by exertion. She halted impetuously as she came opposite to him, and he caught a glimpse of her face—the mobile face of a girl, with parted lips and arresting blue eyes. She was hatless, and, though Hallett could not have described her attire, he got an impression of some soft black stuff, clinging to a slim figure. She surveyed him in a quick, appraising glance, and before he could speak had thrust something into his hand.

‘Take it—run!’ she gasped, and tore forward into the fog.

It had all happened in a fraction of time. She had checked rather than halted in her flight. An exclamation burst from Hallett’s lips, and he was almost startled into obedience of the hurried command. Then heavier footsteps thudding near brought him to himself. He moved to interrupt the pursuer. As a man came into view Hallett’s hand fell on his shoulder.

‘One moment, my friend—’

An oath was spat at him as the man wrenched himself free and was blotted out in the gloom. Hallett shrugged his shoulders philosophically, and made no attempt at pursuit.

‘Alarums and excursions!’ he murmured. ‘Wonder what it’s all about?’

In nine-and-twenty years of life, Jimmy Hallett had acquired something of a philosophy that made him content to accept things as they were, save only when they affected his personal well-being. Then he would sit up and kick with both feet. His lack of curiosity was almost cold-blooded. There was, indeed, a certain inoffensive arrogance in his attitude towards the ordinary affairs of life. He was the sort of man who would not cross the road to see a dog-fight.

Yet he always had a zest for excitement, providing it had novelty. A man who had scrambled for a dozen years in a hotch-potch of vocations retains little enthusiasm for commonplaces. When Hallett senior had gone out from the combined effects of a Wall Street cyclone and an attack of heart failure, his son and heir had found himself with a hundred thousand dollars less than nothing. Young Hallett went to his only surviving relative—an elderly uncle with a liver—and, with the confidence of youth, rejected the offer of a cheap stool in that millionaire’s office. He believed he could get a living as an actor; but a five weeks’ tour in a fortieth-rate company, which finally stranded in the wilds of Michigan, convinced him of the futility of that idea. After that he drifted over a wide area of the United States. Farmhand, railwayman, cow-puncher, prospector, and one very vivid voyage as a deck-hand on a cattle boat. It was inevitable that, of course, he should eventually drift into that last refuge of the unskilled, intellectual classes—journalism. Equally, of course, it was inevitable that Fate, who delights to take a hand at unexpected moments, should interfere when he showed signs of making a mark in his profession. His uncle died intestate, and Jimmy leapt at a bound to affluence beyond his wildest dreams.

He had stayed long enough in New York after that to realise how extensive and variegated were the acquaintances who had stood by him in adversity. They took pains that he should not forget it. And forthwith he had taken counsel of Sleath, the youthful-looking city editor of ‘The Wire’, who breathed words of wisdom in his ear.

‘Go to Europe, Jimmy. Travel and improve your mind. Let the sharks forget you.’

So Jimmy Hallett stood lost in a fog, somewhere within hail of Piccadilly Circus, with an unopened package in his hand, and the memory of a girl’s voice in his mind. A less observant man than Hallett could not have failed to perceive that the girl was of a class unlikely to be involved in any street broil. The man flattered himself that he was not impressionable. But he retained an impression of both breeding and looks.

He dangled the package—it was small and light—on his finger, and moved forward till the light from a shop window gave him an opportunity of examining it more closely. It was closely sealed with red sealing wax, but the wrapping itself had apparently been torn from an ordinary newspaper. He hesitated for a moment, and then tore it open. He could scarcely have told what he expected to find. Certainly not the thirty or forty cheques that lay in his hand. One by one he turned them slowly over, as though the inspection would afford some indication of why they had been so unexpectedly thrust upon him. A bare possibility that he had been made an unwilling accomplice in a theft was dismissed as he noticed that the cheques were dead—they all bore the cancelling mark of the bank. Why on earth should the girl have been running away with the useless cheques? And why should she have so impulsively confided them to a stranger to prevent them from falling into the hands of her headlong pursuer?

Not that Hallett would have worried overmuch about these problems had the central figure been plain or commonplace. She had interested him, and his interest, once aroused in any person or thing, was always vivid.

Keen-eyed, he scrutinised the cheques in an endeavour to decipher the signature. They were all made out by the same person, and payable to ‘self’. The name he read as J. E. Greye-Stratton. Whoever J. E. Greye-Stratton was, he had drawn within three months, in sums ranging from fifty pounds to three hundred pounds, an amount totalling—Hallett reckoned in United States terms—more than fifteen thousand dollars.

He stuffed the cheques into his pocket as an idea materialised in his mind. An opportune taxi pushed its nose stealthily through the wall of fog and halted at his hail.

‘Think you can find a post-office, sonny?’ he demanded.

‘Take you anywhere, sir,’ assented the driver, cheerfully.

‘Find your way by the stars, I suppose,’ commented Hallett, the tingle of fog still in his eyes.

Nevertheless, the driver justified his boast, and his fare was shortly engrossed with the letter ‘G’ in the London Directory. There was only one entry of the name he sought, and he swiftly transcribed the address to a telegraph form.

‘Greye-Stratton, James Edward, 34, Linstone Terrace Gardens, Kensington, W.’

Shortly the cab was again crawling through the fog, sounding its siren like a liner in mid-channel. All that the passenger could make out was a hazy world, dotted with faint yellow specks, which now and again transformed themselves into lights as they drew near them. Later the yellow specks grew less as they swerved off the main road, and a moment later the car came to a halt.

The driver indicated the house opposite which they were standing, with a jerk of his thumb, as Hallett descended.

‘That’s the place, sir.’

It was little that Hallett could see of the house, save that it was a big, old-fashioned building, with heavy bow, windows and a basement protected by wrought-iron rails. There was no light in any part of the house, not even the hall. Twice the young man wielded the big, brass knocker, arousing nothing apparently but an echo. As he raised it a third time the door was thrown open with disconcerting suddenness, and he was aware of someone standing within the blackness of th

e hall. Hallett could distinguish nothing of his features.

‘I wish to see Mr Greye-Stratton,’ said Hallett, and tendered a card.

The other made no attempt to take it.

‘He won’t see you,’ he declared, with harsh abruptness, and only a sudden movement of Hallett’s foot prevented the door being slammed in his face.

His teeth gritted together, and he thrust the door back and himself over the lintel. He was an easy-tempered man, but the deliberate discourtesy had roused him to a cold anger.

‘That will do, my man,’ he said, clipping off each word sharply. ‘I want ordinary civility, and I’m going to see that I get it. My name is Hallett—James Hallett, of New York. Now you go and tell your master that I want to see him about certain property of his that has come into my hands. Quick’s the word!’

There was a pause. When the man in the hall spoke again his tone had changed.

‘I beg your pardon, Mr Hallett. It is dark—I mistook you for someone else. I am sure Mr Greye-Stratton would have been happy to see you, but unfortunately he is ill. If you will leave whatever you have, I will see that it reaches him. By the way, I am not a servant. I am a doctor. Gore is my name.’

Hallett thrust his hand in the pocket that contained the cheques. He had no intention of handing them over without some information about the girl in black. And he fancied he detected a note of anxiety in the doctor’s voice, as though, while forced in a way to civility, he was anxious for the visitor to go.

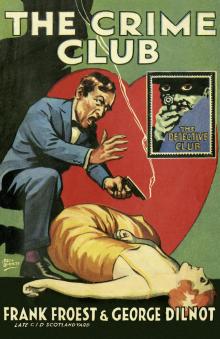

The Crime Club

The Crime Club The Rogues' Syndicate

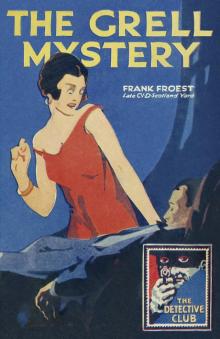

The Rogues' Syndicate The Grell Mystery

The Grell Mystery